Atrial fibrillation is the most commonly diagnosed arrhythmia in the world. Despite that, many women do not understand the pre-diagnosis symptoms and tend to ignore them.

Ignoring medical symptoms can lead to stroke, dementia, early death

A UBC Okanagan researcher is urging people to learn and then heed the symptoms of atrial fibrillation (AF). Especially women.

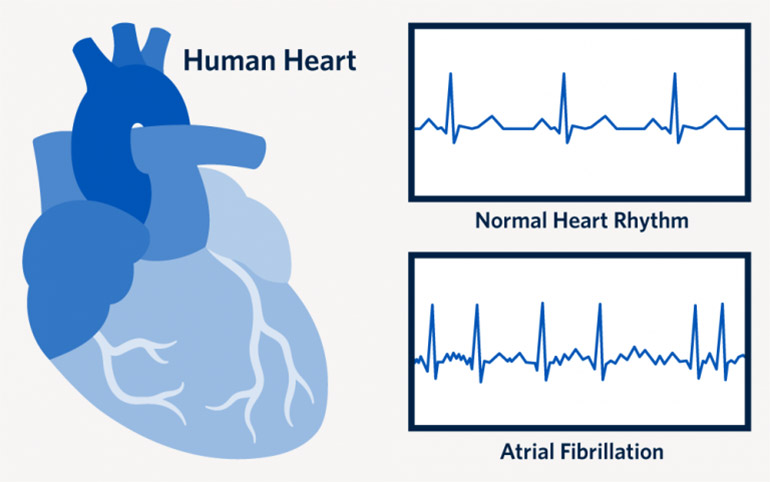

Dr. Ryan Wilson, a postdoctoral fellow in the School of Nursing, says AF is the most commonly diagnosed arrhythmia (irregular heartbeat) in the world. Despite that, he says many people do not understand the pre-diagnosis symptoms and tend to ignore them.

In fact, 77 per cent of the women in his most recent study had experienced symptoms for more than a year before receiving a diagnosis.

While working in a hospital emergency department (ED), Dr. Wilson noted that many patients came in with AF symptoms that included, but were not limited to, shortness of breath, feeling of butterflies (fluttering) in the chest, dizziness or general fatigue. Many women also experienced gastrointestinal distress or diarrhea. When diagnosed they admitted complete surprise — even though they had been experiencing the symptoms for a considerable time.

One in four strokes are AF related, he says. However, when people with AF suffer a stroke, their outcomes are generally worse than people who have suffered a stroke for other reasons.

“I would see so many patients in the ED who had just suffered a stroke but they had never been diagnosed with AF. I wanted to get a sense of their experience before diagnoses: what did they do before they were diagnosed, how they made their decisions, how they perceived their symptoms and ultimately, how they responded.”

Even though his study group was small, what he learned was distressing.

“Ten women, in comparison to only three men, experienced symptoms greater than one year,” says Dr. Wilson. “What’s really alarming is they also had more significant severity and frequency of their symptoms than men—yet they experience the longest amount of time between onset of symptoms and diagnosis.”

What really troubles Dr. Wilson are the reasons a diagnosis is delayed in women.

Many doubted their symptoms were serious, he says. They discounted them because they were tired, stressed, thought they related to other existing medical conditions, or even something they had eaten. Most women also had caregiving responsibilities that took precedence over their own health, and they chose to self-manage their symptoms by sitting, lying down, or breathing deeply until they stopped.

What’s more alarming, however, is that if women mentioned their symptoms to their family doctor, many said they simply felt dismissed.

“There was a lot more anger among several of the women because they had been told nothing was wrong by their health-care provider,” says Dr. Wilson. “To be repeatedly told there is nothing wrong, and then later find yourself in the emergency room with AF, was incredibly frustrating for these women. More needs to be done to support gender-sensitive ways to promote an early diagnosis regardless of gender.”

Dr. Wilson reports that none of the men in his study were upset about their interactions with their health-care providers, mostly because they were immediately sent for diagnostic tests.

“But a delay in diagnosis is not just in this study,” he cautions. “Women generally wait longer than men for diagnosis with many ailments. Sadly, with AF and other critical illnesses, the longer a person waits, the shorter time there is to receive treatments. Statistically, women end up with a worse quality of life.”

Dr. Wilson, who is currently working on specific strategies to help people manage AF, admits the condition is often hard to diagnose because some of the symptoms are vague. Ideally, he would like people to be as knowledgeable about AF as they are about the symptoms and risks of stroke and heart attacks. As the population is living longer, the number of people with AF continues to increase. In fact, about 15 per cent of people over the age of 80 will be diagnosed with the condition.

“People know what to do for other cardiovascular diseases, it’s not the same with AF,” he adds. “And while the timeline may not be as essential as a stroke for diagnosis and care, there is still a substantial risk of life-limiting effects such as stroke, heart failure and dementia. Reason enough, I hope, for people to seek out that diagnosis.”

Dr. Wilson’s study was recently published in the Western Journal of Nursing Research.

About UBC’s Okanagan campus

UBC’s Okanagan campus is an innovative hub for research and learning founded in 2005 in partnership with local Indigenous peoples, the Syilx Okanagan Nation, in whose territory the campus resides. As part of UBC—ranked among the world’s top 20 public universities—the Okanagan campus combines a globally recognized UBC education with a tight-knit and entrepreneurial community that welcomes students and faculty from around the world in British Columbia’s stunning Okanagan Valley.

To find out more, visit: ok.ubc.ca